Why a monorepo? Requirements for a good workflow

Why a Node.js monorepo?

Those who have worked maintaining many dependent packages in different repositories would answer to this question with lots of reasons very quickly. I’ve been dealing with this scenario for many years, and I can tell you that I have suffered it in my own skin. In fact, in the past I have suffered it even when trying to maintain many packages in in the same repository.

I don’t want to have a monorepo just because it is a trend, I want to make a list of the problems that I suffered in the past and that I want to solve, and really check if they would be solved using a monorepo. Let’s the some problems:

Dealing with independent repositories

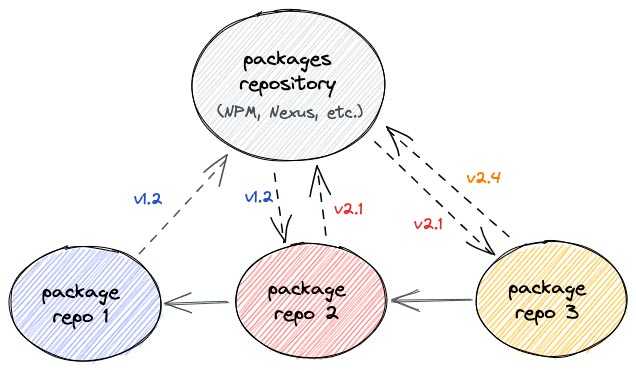

In theory, it is perfectly possible to work in one package independently, then publish it, and then we can go to the other package, upgrade the dependency and continue working on the integration until it is ready, then publish it, and so on… They are different packages because they are independently testable and deployable/distributable, and that’s how they must be. But, in the real world, unfortunately, this workflow is not so easy. In the real world we make mistakes, we don’t define the details of the implementation needed in one package at the sufficient low level, and when we are integrating the next package we realize that we have to make a step back and make a change in the package that we have just published, and then return to the next package again. Suppose that you are maintaining a project consisting on about ten packages, you are running the E2E tests of the last package, and then you realize that you have to modify again the first one… well, I can say that it’s very frustrating, to say the least. Even if everything goes well, the process of release becomes slow and tedious.

And this is only one of the main problems that I have found working with different repositories. Let’s see some more:

- Continuous integration workflow - The workflow for releasing a new version of the package who depends on the others becomes slow and tedious. The mere fact of upgrading a dependency in a “core” package can result in opening lots of pull request in different repositories until we have released new versions of all of the dependencies in series. As mentioned, it may result in a never ending history if we find problems that make us to give steps back again and again.

- Duplicity of dependencies, configuration and tooling - The configuration for the continuous integration workflow is duplicated. The same happens with the development dependencies and some configuration, such as linter configuration, NPM commands, and even documentation. In the practice, we see ourselves using copy-paste more times than we would like.

- Duplicity of testing - Normally, each package should be testing the integration with its dependencies, and this usually ends in duplicating some integration tests in different repositories. Not to mention end to end tests, which usually are heaviest to run and require more tooling, and it could also become duplicated in some of the repositories, making the continuous integration workflow even harder.

- POCs or debugging - Developing fast prototypes for introducing a major change in the system becomes hard when you can only modify one package at a time. This is not necessarily bad, normally we want to introduce changes progressively and in a very controlled way, but the truth is that sometimes we need to probe some concept in a fast way, or we want to debug many packages at a time in an easy way.

Mitigating these problems in the past

Let me make some memory about how we tried to solve some problems in the past, because it may be useful to check if all of these problems are really solved using the tools that we have now. During years we all have found different ways for mitigating one or another problem from the list above using different “hacks”, but the truth is that usually, when you mitigate one, then the other gets worse.

Let’s see some examples. I have named some of them as “pseudo workspace using x”, so, first of all, what I mean by “pseudo workspace”? Well, by “workspace” I refer to the feature of linking dependencies between the packages in a repository, so it does not install the dependency from the remote repository, but from the code of the other package in the repository at that moment. That’s what today is named a workspace in NPM and Pnpm, for example. It allows to make changes in one package and see them in the other packages in the repository without the need to release a new version. As years ago I didn’t know about a real workspace tool, I have tried by myself all of the next approaches, usually with bad results:

- Pseudo workspace using

npm link- Npm provides alinkcommand since many years ago for linking packages locally, but it required to execute it locally for each package that you wanted to link or unlink, and there was no way to define those dependencies in a configuration file. The symlinks were created globally, and in my experience, it produced many issues. (I don’t know if has been improved by today). - Pseudo workspace using

local paths- As of NPM version 2.0.0 you can provide a path to a local directory that contains a package. The approach was very similar to the previous one, but with the improvement of defining the local dependency in thepackage.jsonfile. It also produced undesired changes in thepackage-lock.jsonfiles and lots of other issues that also made hard to work with it. I even published my own tool providing a command line interface to link packages easier usinglocal pathsunder the hood (now the package is pending to be deprecated). - Overwriting code in

node_modules- Really? Well, not as a part of the usual workflow, but to be honest, sometimes I found myself overwriting a package in thenode_modulesfolder in order to run some integration tests prior to publish it. 😞 - Publishing to a private registry - Maybe you know the Verdaccio local NPM registry project (or even the deprecated Sinopia, if you are as old as I am 😉). Well, these projects provide a local NPM registry that allows us to publish one package locally, then we can install it in the next one, and so on, so it solves partially the local development and integration workflow problems mentioned above. That if we set up a local registry, we take care of the order in which packages have to be published, etc. In my experience, the local development becomes a crazy thing when you have to deal with many packages, publish/unpublish or republish different versions, clean caches, etc. Not to mention the complexity of the pipelines if we keep the code in different repositories, then you’ll probably have to define which repository pipelines trigger other ones where you’ll probably have the integration tests, etc. That, supposing that the NPM private registry is ephemeral, because I worked in a project in which it was not ephemeral, it was allowed to unpublish packages, and continuous integration pipelines were continuously overwriting packages versions. I don’t get nostalgic when I remember those days.

- Using Babel aliases - Using Babel or TypeScript aliases allows to change the

importreferences, so when you import one package from another, it loads the one from the local workspace instead of the one downloaded by the NPM client. This is the approach that worked better for me, but it still requires some manual configuration for each package, and I don’t like to always have to build my code just for these types of requirements. In fact, we’ll see that this approach can still be used with some tools as Nx if you don’t use Pnpm or other workspace tool.

All of these methods and “hacks” talk about solving the problem of linking dependencies locally to avoid having to publish packages before building the others or running the integration tests, but none of them talk about solving another “problem” created by a monorepo:

If we have everything in a repository, we’ll have to test everything every time we try to promote the code, until we have a method for detecting which packages have been modified and which ones depends on them.

Should we give up?

At this point someone could say, “Well, if having different packages produces such problems, why not to have all of the code in one single package in one repository?”. The answer is simple: because we don’t want to have a monolithic package, we want to solve all of the mentioned problems in the workflow, but keeping isolated each package to be able to distribute it independently, and continue testing it independently, apart of running the appropriate integration tests when correspond.

In the next chapters we will see that most of the problems have been already solved if we choose the appropriate tools. But first, let’s recapitulate a list of requirements to avoid the inconvenience mentioned above.

Requirements for a monorepo

Based on my ugly experiences described above, we can see that a monorepo is not just about “code colocation”. It should solve the real underlying problems that we find when working with many dependent packages or projects. So, here is my list of “must have” requirements for a good workflow:

- Configuration for linking dependencies locally - The monorepo tooling should provide a way to link dependencies. Locally the code of the other packages in the repository should be loaded from the repository itself, but it should still be versioned and downloaded from a binary repository when packages are published.

- Dependencies analysis - It should be able to understand the dependencies between the projects in the repository without extra configuration.

- Detecting affected packages/projects - It should determine which projects might be affected by a change in the repository, to build or test only those. By “affected” projects I mean modified projects, or projects that depend on those modified at any level.

- Task orchestration - Based on the repository dependencies, it should be able to run tasks in the correct order. Integration tests can’t be executed before building all needed projects first, for example.

Choosing the appropriate tools

Now that we have the list of minimum requirements, we can look for the appropriate tools to satisfy them all. At this moment there are many tools for working with monorepos, and the list is increasing quickly.

At this point, you can check the monorepo.tools webpage, which provides a good explanation about what a monorepo should be, and a larger list of requirements. Here I have included only those which I consider strictly necessary, and I have omitted those which I consider only “nice to have”. The site also includes a list of monorepo tools with a comparison of their features.

I’m not going to make a comparison between tools here, so I will focus in two tools that I am currently using with good results. We will see how these tools meet the mentioned requirements.

Pnpm

Using Pnpm we will meet the first one criteria: “Configuration for linking dependencies locally”. It includes a workspace feature which is able to link packages locally, and it does the job pretty well. It also changes automatically the linked dependencies to the desired version when the package is published, with support for pinned dependencies or semver ranges. As a brief summary, it is able to:

- Link packages locally

- Publish all packages with a single command. It skips those which version already exists. (This is very useful in continuous integration, as we will see in the next chapters)

- Save disk space and boost dependencies installation speed. (A great point when talking about NPM dependencies)

Nx

Nx provides to us the other needed features. It is a monorepo tool that is able to make a dependencies analysis, detect affected projects, and orchestrate tasks. As an extra, it is plugabble, and it provides boilerplates to create monorepos for some specific libraries or frameworks, such as React, Angular, etc. But I personally prefer to use only the core features in order to avoid coupling my projects too much to a specific technology or plugin. Among other things, it provides:

- Dependencies analysis

- Detection of affected projects

- Task orchestration

- Dependency graph visualization

- Parallelization of tasks

- Local computation caching

- Pluggable

Conclusion

In this post we have seen some problems that were common in the past when working with many dependent packages and some methods or “hacks” that tried to mitigate them. We also have seen how using a monorepo with the appropriate tools might solve those problems. After choosing the tools based on the requirements, in the next chapters I will provide examples about how to configure them to create a complete continuous integration workflow using Github Actions that will make our life as developers easier (at least it did in my case 🙂).